By Michael Lipka May 13, 2015

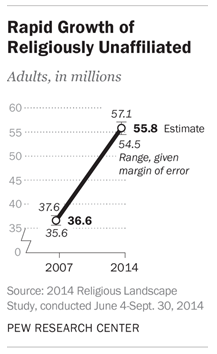

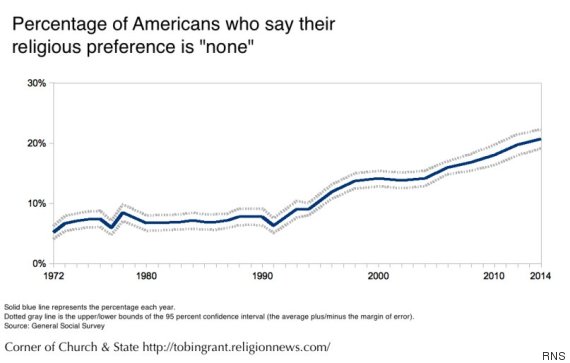

Religiously unaffiliated people have been growing as a share of all Americans for some time. Pew Research Center’s massive 2014 Religious Landscape Study makes clear just how quickly this is happening, and also shows that the trend is occurring within a variety of demographic groups – across genders, generations and racial and ethnic groups, to name a few.

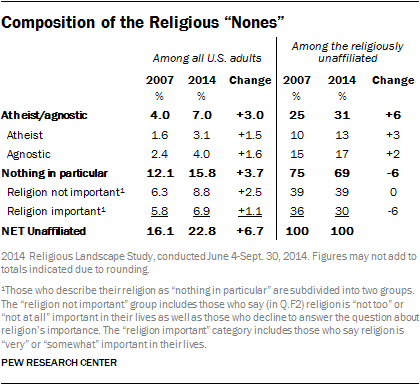

Religious “nones” – a shorthand we use to refer to people who self-identify as atheists or agnostics, as well as those who say their religion is “nothing in particular” – now make up roughly 23% of the U.S. adult population. This is a stark increase from 2007, the last time a similar Pew Research study was conducted, when 16% of Americans were “nones.” (During this same time period, Christians have fallen from 78% to 71%.)

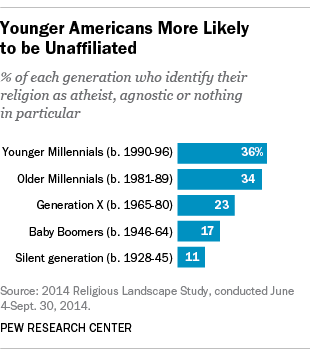

Overall, religiously unaffiliated people are more concentrated among young adults than other age groups – 35% of Millennials (those born 1981-1996) are “nones.” In addition, the unaffiliated as a whole are getting even younger. The median age of unaffiliated adults is now 36, down from 38 in 2007 and significantly younger than the overall median age of U.S. adults in 2014 (46).

At the same time, even older generations have grown somewhat more unaffiliated in recent years. For example, 14% of Baby Boomers were unaffiliated in 2007, and 17% now identify as “nones.”

”Nones” have made more gains through religious switching than any other group analyzed in the study.” Only about 9% of U.S. adults say they were raised without a religious affiliation, and among this group, roughly half say that they now identify with a religion (most often Christianity). But nearly one-in-five Americans (18%) have moved in the other direction, saying that they were raised as Christians or members of another faith but that they now have no religious affiliation. That means more than four people have become “nones” for every person who has left the ranks of the unaffiliated.

“Nones” are more heavily concentrated among men than women. But the growth of the unaffiliated has not been limited to certain demographic categories; a rise in the share of unaffiliated has been seen across a variety of racial and ethnic groups, among people with different levels of education and income, among immigrants and the native born, and throughout all major regions of the country.

Not only are the “nones” growing, but how they describe themselves is changing. Self-declared atheists or agnostics still make up a minority of all religious “nones.” But both atheists and agnostics are growing as a share of all religiously unaffiliated people, and together they now make up 7% of all U.S. adults (up from 4% in 2007). Nearly two-thirds of atheists and agnostics are men, and the group also tends to be whiter and more highly educated than the general population.

In addition to atheists and agnostics, another 9% of Americans say their religion is “nothing in particular” and that religion is not important in their lives. At the same time, however, a significant minority of “nones” say that religion plays a role in their lives. Indeed, about 7% of U.S. adults say their religion is “nothing in particular” but also say that religion is “very” or “somewhat” important in their lives, despite their lack of a formal affiliation. This group is more racially and ethnically diverse than other “nones”; only 53% are non-Hispanic whites (compared with 66% of the general public).