People gather for the Reason Rally on the National Mall in 2012 in Washington, D.C.

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP/Getty Images

Jenny Schulz isn’t religious.

“I see religion as something really personal,” said Schulz, 26, who works at a nonprofit in Washington, D.C. “So the fact that it is a requirement in politics always seems unusual to me.”

She said she “oscillates between atheist and agnostic,” but she knows it could be many years before she votes for a political figure who shares her (lack of) religious beliefs.

Schulz is not alone. She is part of a growing group of American adults who do not identify with any religion. More than one-in-five American adults say so now, the highest in U.S. history. They are being identified as the religious “nones,” so called for their lack of religious affiliation. As they grow in size, they are also gaining political power.

“I personally think that the characteristics, the profile, the potential influence of religious ‘nones,’ who say they have no religion, is an often overlooked part of the religion in politics story,” said Greg Smith, associate director of research at the Pew Research Center.

Those “nones” consist of atheists, agnostics, and people who simply say they subscribe to no religion in particular. Altogether, they make up nearly 23 percent of the adult population, according to Pew.

That’s more than than Catholics, and nearly as many as evangelicals, at 25.4 percent, according to the most recent Pew Religious Landscape Survey. Between just 2007 and 2014, the adult population of “nones” skyrocketed by 52 percent, to nearly 56 million. And that growth makes the “nones” one of the biggest, but least-noticed, stories in American politics, Smith said.

“When we think about religion in politics we often think about evangelicals,” Smith said. “We often think about the religious right. We think about conservative Christians — and those are important groups. But we also have this large and growing group in the U.S. that say they have no religion. And that group is a kind of a counterweight at the other end of the religious spectrum from evangelicals.”

He points to the 2012 election as an example. White evangelicals voted overwhelmingly for Republican nominee Mitt Romney, 79 to 20 percent. But people who claimed no religious affiliation voted overwhelmingly for President Obama — 70 percent to 26 percent.

Nonreligious Politicians Are Remarkably Rare

Schulz is so used to politicians invoking God in one way or another that she really doesn’t think much about it.

“It doesn’t rub me the wrong way. I just see it as a given: In order to run for office in the U.S., you have to play up the religious side,” she said. “That’s the perception I’ve always gotten.”

It’s easy to see why she would think that. There has never been an avowedly atheist president of the U.S., and only two have been unaffiliated with any religion, according to Pew — Thomas Jefferson, who, while fascinated by Jesus’ teachings, was considered a deist, and Abraham Lincoln, whose religious beliefs remain a topic of debate.

And, as of January, only one member of the current Congress reported being religiously unaffiliated. (An additional nine said they didn’t know or refused to answer).

Of course, there are a few other reasons why so few politicians pander to the “nones” and so many are appealing to the evangelicals that Smith mentions as their “counterweight.” One is that the religiously unaffiliated are still a pretty diverse group, meaning appealing to all — or even most — at once on a broad spectrum of issues is difficult.

For example, some still have some sort of belief in a god, and around one-third to one-quarter of them say religion is still “important” to some degree to them. Just under half of these unaffiliated people go to church sometimes, for example (though it’s less often than for the religious). And then there are the atheists, the agnostics and those who simply say religion isn’t important to them. Together, that group of the least religious people in America makes up around one-in-seven Americans.

“They may be unaffiliated; they may be atheist; they may be agnostic … but they’re not part of some club,” says Margie Omero, a Democratic strategist at Purple Strategies. “You could certainly argue that evangelicals are not monolithic in terms of their policy beliefs, but there’s no denying that there’s more of an organization around organized religion than there is around disorganized atheism.”

So could a group defined by its lack of religious definition in any way be considered a cohesive voting bloc?

“Yes and no,” said Todd Stiefel, chair of Openly Secular, a nonprofit that encourages nonbelievers to be more vocal.

“I think we are a voting bloc on some issues. Marriage equality, pro-choice, the separation of church and state. Those are issues where, yeah, we’re pretty much a voting bloc,” Stiefel said. “On other issues, it’s complicated,” he added, noting that nonreligious Americans range from fiscally liberal to conservative.

And then there’s another huge reason politicians and pundits pay such close attention to the religious compared to the unaffiliated: the “nones” are underrepresented at the polls. For example, the religiously unaffiliated are almost even with white evangelicals in the broader population today, but the “nones” made up only 12 percent of the electorate in 2012, compared to white evangelicals’ 23 percent. In other words, they’re less likely to vote.

Americans Don’t Want To Vote For Atheists

Americans also really, really like voting for religious people. In a 2014 Pew poll, 53 percent of Americans said they’d be less likely to vote for an atheist (only 4 percent said they’d be “more likely”). Yet another poll found that 53 percent of Americans believe that it’s necessary to believe in God to be moral. Being religious is simply good politics.

Indeed, on the 2016 campaign trail, virtually all of the candidates bring up religion. When she happened upon a man reading his Bible at a bakery on the campaign trail this year, Hillary Clinton talked God with him, remarking that the Bible is the “living word.”

Scott Walker has likewise played up his religious beliefs more on the presidential campaign trail than during his early political career in Wisconsin, as the New York Times has reported. The only major presidential candidate who is not openly religious is Bernie Sanders. He is Jewish, but has made a point of saying he is not practicing.

But even with all of the public displays of religion, you can already see politicians playing to a less religious electorate. Republicans, who fare poorly among the “nones,” are subtly tailoring their messages for an increasingly secular nation.

“You’re already seeing Republicans, in particular, take this into account, and you’re seeing it with gay marriage,” said Ford O’Connell, a Republican strategist who worked for the McCain-Palin campaign in 2008, chair of CivicForumPAC, managing director of Civic Forum Strategies and author of Hail Mary: The 10-Step Playbook for Republican Recovery. “What you’re starting to see is Republicans significantly changing their tone and rhetoric. … For example, on gay marriage — they’re couching it as ‘religious liberty,’ which sounds less divisive.”

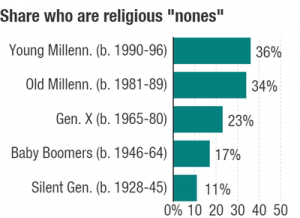

And while they may not be a huge force in 2016, the “nones” are still growing, and they’re doing so by the power of replacement. The younger the person, the less likely they are to claim a religion. Thirty-six percent of young millennials are religiously unaffiliated, compared to just 11 percent of the silent generation. Not only that, but the group’s members are increasingly identifying as atheist and agnostic, while the share who consider religion at all important to them is falling.

The incoming wave of nonreligious Americans could mean a tipping point in the Republican Party’s platform of social issues.

“The real question for the Republican Party is will this trend continue and will it continue at this rate?” O’Connell said. “I can see them changing their views on not so much abortion but other related issues [like same-sex marriage] by 2024.”

Why 2024? Because that’s when today’s millennials will be entering middle age, replacing today’s Gen-Xers and baby boomers. As millennials marry, settle down and have kids — things they’re doing later than their parents — he thinks there’s a possibility they will shift rightward. The GOP does better among married women than single women, he points out (though his logic assumes that marriage could make a person more conservative, not just that conservative women might be more likely to be married to begin with). And once people marry, he added, more-religious people might end up bringing their less-religious partners into the church.

But those are big ifs. The growing share of “nones” may not care whether their politicians are religious, as Schulz said she doesn’t. But they could mean a voting population that increasingly doesn’t care if their politicians aren’t.